Is ‘overdiagnosis’ a price worth paying in melanoma?

A 45-year-old woman presents for a skin examination. The patient is routinely asked if there are any new or changing lesions of concern.

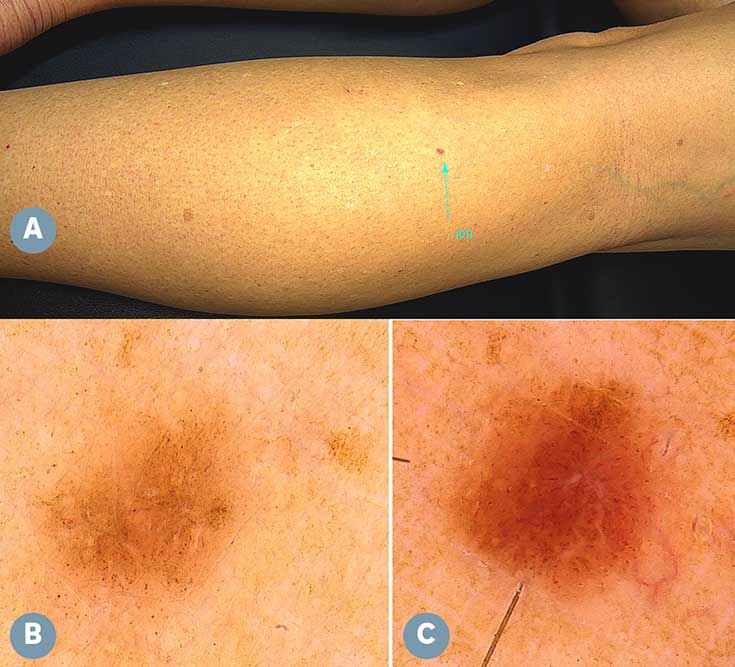

She mentions that a minute lesion on her left leg has appeared since her last visit (figure A).

Dermoscopy reveals a pigmented lesion that is 1.5mm in diameter. It has no chaos or compelling clues to malignancy and is not at the examiner’s threshold for excision biopsy (figure B).

The lesion is photo-documented and the patient asked to return for review in six months.

At the follow-up review, reimaging reveals significant dermatoscopic changes, including a doubling in size, marked asymmetry and the clue to malignancy of white lines (figure C).

Excision biopsy reveals a thin invasive melanoma, 3mm in diameter, with a Breslow thickness of 0.3mm.

Discussion

As more small melanomas are diagnosed, the fact that every melanoma starts as a microscopic lesion is increasingly evident.

It has been argued that targeting small or indolent melanomas amounts to ‘overdiagnosis’ — that is, the diagnosis of melanomas that would never cause harm during the lifespan of the patient.1

Epidemiological ‘overdiagnosis’ is not the same as ‘misdiagnosis’, whereby an error is made and a person is wrongly labelled as diseased when they are not; or ‘overcalling’, whereby a disease precursor is ‘upstaged’.

New evidence from the Australian Cancer Atlas illustrates graphically that the precise regions with the highest rate of melanoma diagnosis — which likely have the highest rate of ‘overdiagnosis’ by well-trained doctors looking for melanomas — also have the highest relative survival from melanoma.2

One possible deduction is that currently ‘overdiagnosis’ is a price paid to improve survival.

In the future, we may have access to new technologies that reliably identify aggressive from indolent melanomas, but we are not there yet.

| Practice Points |

|

Interested in learning more about dermoscopy?

Professor Cliff Rosendahl is a GP with a special interest in skin cancer. He has academic appointments at the faculty of medicine, University of Queensland, and at the school of medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Professor David Whiteman is a medical epidemiologist, with a special interest in the causes, control and prevention of cancer — in particular skin and gastrointestinal cancer. He is acting director at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, and a fellow of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences.

References: