Why Christians are adopting 30-year-old human embryos

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The world’s media declared Thaddeus Daniel Pierce the “world’s oldest baby” after his birth via IVF from a 30-year-old frozen embryo, but his status as the oldest embryo carried to birth was merely part of the story.

In the ’90s, Thaddeus’ biological mother had one child via IVF and retained three frozen embryos, even fighting a legal battle to keep them after divorcing the father.

However, she never felt financially prepared to give birth again.

A Christian group called the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption Program then connected Thaddeus’ biological mother and his adoptive parents, leading to Thaddeus’ birth in July this year.

Snowflakes, a division of a wider group called Nightlight Christian Adoptions, follows the belief that life begins at conception and that all embryos, including those created through IVF, deserve to be born.

“Many of our placing families are Christian, but those who are not still generally recognise the embryos as life and they want to choose a life-giving option for their remaining embryos,” said Elizabeth Button, Snowflakes executive director.

Snowflakes began in 1997 and the number of frozen embryos in the US has since increased hugely.

In 2016 it was estimated there were somewhere between 400,000 and 1.4 million frozen embryos being stored in the US.

Ms Button said Snowflakes had organised 150 donations to adoptive families in 2024.

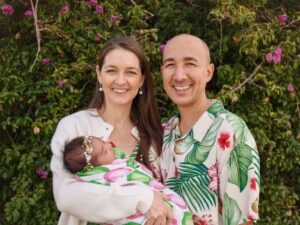

In 15 years, seven Australian families had adopted embryos via Snowflakes, including Perth couple Brad and Siobhan Page, who have had four children through the program.

As newlyweds, they discovered they were unable to conceive due to fertility issues and that traditional adoption was harder to access than expected.

They did not want IVF based on their Catholic faith but having that discussion prompted them to explore more options.

“We were listening to a talk on YouTube about infertility and Catholic marriage, and the topic of IVF was touched on,” Ms Page told AusDoc.

“They talked about it as an available fertility treatment that you might be tempted to do and then why the Church preaches against it, which was nothing new to us.

“Then they said: ‘And that is not even considering the problem of all the embryos in frozen storage that have an uncertain fate.’

“I went, ‘Yeah, what about those frozen embryos? There must be millions.'”

The Catholic Church does not have a formal stance on embryo adoption.

Some Catholics have argued that providing a life for frozen embryos, ensuring they are not discarded, is a good deed. Others have argued it inappropriately endorses IVF.

Mr Page said Australian services were limited to individual IVF clinics or social media groups that felt like “Gumtree for embryos”, while Snowflakes felt “humanist”.

But Snowflakes also required adopting couples to have been married for at least two years, so the newlywed Pages waited.

“We spoke to a lot of people about the ethics of this,” Mr Page said.

“We spoke to our family to see if they would be supportive, to our friends, to spiritual advisers, bioethicists, and we even tried to speak to people who we thought would talk us out of it.

“For us, the problem is when you are producing a child for self-serving purposes.

“What is good about adoption is that you are taking a kid who is needy and you are raising a family.”

Finally, in 2019, they applied to Snowflakes.

Like traditional adoption, the process involved education on parenting adopted children. They also needed an endorsement from a social worker.

Their profile for Snowflakes to share with donors covered their medical history, faith, hobbies, jobs and how many children they wanted to have.

That last point was important.

If donors had multiple embryos, Snowflakes wanted as many as possible to reach the same adopters.

Ms Page, then 33, hoped she and her husband would have at least three children.

Then they were connected to a family with nine embryos based on compatibility.

Ms Page said that accepting a group of embryos did not mean a guaranteed number of pregnancies, as some embryos could die during thawing. But while they could end up with no children, they could end up with nine children.

The couple signed a contract giving them ownership of all nine embryos.

Eight came in pairs, meaning a single transfer possibly meant twins.

The Pages agreed that the embryos they did not attempt to use would be returned to the donors.

“We thought we could definitely have three children from nine embryos and, after that, we would see what happened — God willing, you know?” Ms Page said.

They travelled to a US clinic that had partnered with Snowflakes. The alternative was shipping frozen embryos to WA — a legal minefield.

Ms Page’s Australian reproductive specialist was initially unsure, albeit curious, about the couple’s choice. However, they became more supportive throughout the subsequent pregnancies, she said.

In 2019, Ms Page had twins from the first duo of embryos, four years after they had been frozen.

The couple thawed two more embryos in 2022 but refroze one after medical advice to avoid a second pregnancy with twins.

They eventually used this refrozen embryo for Ms Page’s fourth and most recent child in 2024.

The only non-paired embryo did not survive thawing, leaving the Pages with four embryos in two pairs still in storage in the US.

Ms Page said it was likely she would not have another child, but the couple was yet to rule out the idea and hand back the embryos.

“We are probably statistically extraordinary to have three embryo transfers, four children and only one embryo not survive,” she said.

They did not plan to hide their children’s origins from them, she said.

“We keep photographs of their genetic family in our home. We talk about them, try to bring it up naturally.”

Fertility lawyer Stephen Page — no relation — said no organisations like Snowflakes existed in Australia, with the smaller population one reason.

“We are seeing this idea of embryo adoption becoming more accepted here, but the number of embryos and storages is much greater in the US,” said Mr Page, a board member at the Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Most Australian states and territories also limit how long donated embryos can be stored, with provisions to authorise extensions. In WA, the limit is 10 years.

Stephen Page said these laws reflected concerns about possible psychosocial effects on these children.

For example, children could be distressed to understand their biological parents had aged decades since their conception.

However, Ms Button said Snowflakes had no evidence suggesting this was the case.

“Yes, Thaddeus and other children who were frozen for so long will have an interesting story to tell about how they joined their family,” she said.

“But whether a child was frozen as an embryo for 10 years or 30, there is no difference in the amount of psychological distress they may experience.

“In fact, there is no evidence to suggest that developing from a frozen embryo affects them psychologically at all.”