Laxatives, laudanum and lancing: What did Aussie GPs do back in 1875?

It’s undergone a change of location and has been subjected to the transformations demanded by modern architectural tastes: the flat grey facade, the polished glass adorned with the squiggled abstractions of the IPN logo.

But the Andrew Nash Clinic, based in Newcastle, NSW, carries historical significance: it’s believed to be the oldest continuously running GP clinic in Australia, a practice dating back before the MBS care plan, before the machine that went ping, before the therapeutic wonders of insulin and penicillin.

The year it opened? 1875.

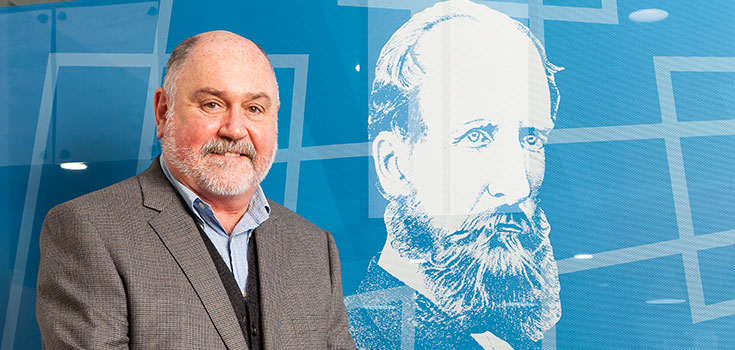

“I don’t know for certain its the oldest,” Dr Brad Bitossi tells Australian Doctor. “I guess I’m throwing it out there and would love to hear from anyone else if they know otherwise.”

Read more:

Dr Bitossi has worked at the clinic for 26 years. He says over that time, they have received dozens of letters addressed to Dr Nash from patients assuming the founding doctor still has a consultation room and a few free slots on his patient list.

“We always knew who he was and some of the history was written in a book about the local hospital by a retired matron,” Dr Bitossi says.

“So we’ve set up a display at our practice telling the story, with some medical artefacts from those times.”

It includes an image, taken from an etching, of Dr Andrew Nash himself.

He looks the typical Victorian gent: the large beard, the high forehead and slightly mad eyes.

Born in Ireland, Dr Nash first arrived in Melbourne in 1857, and subsequently moved to NSW in response to a newspaper ad in The Sydney Morning Herald, calling for a doctor to care for the local colliery.

The ad guaranteed 600 patients — miners, workmen and their families.

“We have no idea what records were kept by the Nash family or even if medical records were common at the time,” Dr Bitossi says.

“So we don’t know precise details of the medical conditions he was dealing with or what he was offering in terms of treatment.

“And we don’t know about pricing and incomes, but do know the lodge system was in place and believe patients paid a periodical sum to be patients of the practice.”

So what was it like back then?

Dr Nash, however, does provide an excuse to ask what general practice looked like in Australia circa 1875. Professor Chris Hogan, one of the RACGP’s historians, admits it was probably “pretty rough”.

Or, as he also puts it, it was probably lots of “laxatives, laudanum and lancing”.

“Doctors in the community would have done surgery — including for fractures and other trauma, appendicectomies, obstetric and gynaecological problems,” he says.

“And they may have been involved with the beginnings of cancer surgery.

“But, obviously, they wouldn’t have had a lot in the way of local anaesthetics — nitrous oxide was first used as an anaesthetic in 1844, followed by ether and chloroform in 1846 — so it would have had to be done quickly.”

Read more: A short history of anaesthesia: from unspeakable agony to unlocking consciousness

As now, but probably without the risks of attracting letters from the chief medical officer, opioids were also a treatment option for doctors. Heroin was the preference in palliative care and childbirth because it was effective and tolerated.

“There was also Brompton’s cocktail for people with terminal illnesses. It was very effective for the simple reason that there was little else, and it worked for most people.

“It was made from heroin or morphine, cocaine, and highly pure ethyl alcohol — though some recipes specify gin — sometimes with added chlorpromazine to counteract nausea.

“It was still in use when I graduated in 1975.

“Cocaine was used mainly in palliative care to raise mood, as a topical application for a local anaesthetic, and it was used in a paste packed into the nose to stop bleeding.”

And in terms of the therapeutic armoury, there was quinine for malaria. Perhaps one of the first wonder drugs, it had a cure rate of more than 98%.

“Sadly, there is only a slight difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic dose. Adverse effects with its use are substantial. The common side effects included cinchonism, hypotension if the drug is given too rapidly, venous thrombosis and hypoglycaemia, particularly in pregnant women.”

The lack of antibiotics, as modern medicine is rediscovering for itself, was also an issue. Mercury was a common treatment for syphilis, the disease that haunted the Victorian imagination, just as it ravaged the Victorian body, with its widespread curses, including madness and congenital blindness.

Although it could delay the symptoms, people would often die either from the disease or its treatment, Professor Hogan says.

“As a student, I would encounter very old patients who had been treated with mercury injections … this had a particular appearance on X-ray with a radio-opaque mass in the buttocks and thighs.

“My teachers would quote this as evidence of the patient having spent ‘an evening with Venus — the goddess of love — and a lifetime with Mercury’.”

And, it’s worth pointing out, that in 1875, scratches and cuts could potentially have been fatal.

“I think the whole philosophy of the time was summed up in the idea of a Celtic prayer which said, ‘May I have a full recovery or a quick death’.”

But also, bear this in mind: as a result of the ‘get better or die’ outcomes, there was no chronic illness.

Dr Hogan says Dr Nash, who was probably seeing between five and 20 patients per day, would have also commanded “extraordinary” respect.

The question for modern-day doctors saturated in the evidence base is why — given half the interventions didn’t work and in some cases probably did do harm?

“The answer lies in the question,” Dr Hogan says. “Half the treatments did work, which was a lot different from times before, when there was universal death.

“Doctors were respected because there were trying their best to learn, to teach. They were educated past primary school when very few were. They were actively involved as community leaders — as Municipal Officers of Health, shire councillors, active correspondents to newspapers, innovators and as informal researchers.

“Their opinion was valued as they were expected to give a reasoned and logical response based on their considerable practical experience and the unspoken acknowledgement that they were the repository of a great many secrets from the town.”

Read more:

- A tribute to Australia’s longest practising doctor — Dr Neville Rothfield

- French GP, 98, has no plans for retirement

While our treatments may have changed and improved, Dr Hogan says there are things to be learnt — the aspects of medicine that have stayed the same throughout history.

“If I were putting my health in the hands of someone like Dr Nash, I would be certain they would do the best they could with what they had, like any of us.

“Our predecessors were highly proficient in the skills we needed when there was nothing we could do to affect the course of disease, injury and frailty. This is a stage that has existed since the beginning of the caring arts; doctors then just reached that point a little earlier in the therapeutic journey than we do now.

“We learnt to sit by the bedside, to give hope where it was necessary and peace where the only hope we had was not from this world or was the eternal rest of death.

“And at that stage … you’ve just got one human being trying to comfort another human being through the last journey of their lives.”

Not much is known about Dr Nash’s views on his own practice, or his knowledge base, or whether he had much insight into what was about to come.

The latter half of the 19th century appears to have been a time when medical revolution was rumbling, even if it was yet to break the surface.

Was Dr Nash interested in the work that had been recently published on the pathology of infection by the French biologist Louis Pasteur?

Had news reached him through the journals and medical debate about Dr John Snow’s investigations into the Broad Street public water pump back in London?

To put it another way, was Dr Nash old-school, a believer in ‘miasma’ as the cause of much of the misery around him?

Or was he at the cutting edge, embracing the new concepts of germ theory, perhaps the biggest medical revolution of all, the one about to lead to the golden age of bacteriology when the actual organisms that cause many diseases would be identified?

Read more:

No, we don’t know. What we do know is a little more mundane. In the days before public health campaigns warning of the health menaces of alcohol abuse, Dr Nash was a partner in a local brewery business, like some other doctors of his time. He was a relatively affluent man.

Tragically, he was killed in 1885, aged just 51. A president of the Wallsend Jockey club, he had been exercising a racehorse called Satellite, his favourite apparently, when it fell and he was crushed beneath.

But his death suggests some things don’t change even if the medicine does: as a GP, he was clearly loved by the community.

Around 4000 people attended his funeral.

The obituary in The Singleton Argus described him as “a doctor whom everyone loved for his skill, kindness and unremitting attention when sickness or care racked the brain and shattered the constitution”.

And like many doctors, his family carried on the tradition. His two sons both became doctors, taking on the practice after his death and into the brighter lights of the 20th century.

“It is not how long but how well we live,” Dr Hogan says.

“It is our duty as doctors to help our patients live a little better than they otherwise would.

“Given the severe limitations under which they practised, are we much better than our colleagues of a century ago? In truth, I do not know.”